Where feedback goes to die

I have a cabinet above my espresso maker where unused gifts go to sit. For each gift I said thank you, and it felt disrespectful to later throw them away, so they sit there for years. Acknowledged yet untouched; quietly accumulating.

The cabinet is what we used to jokingly call write-only storage. A physical manifestation of gratitude and obligation, but really just a way of postponing honesty. There are ideas, observations, and judgments we receive in much the same way: politely accepted, carefully stored, and just as carefully kept from interfering with how we live.

Feedback often ends up there. Thank the person offering it, assume good intent, reassure ourselves that we’ve heard it. And then place it somewhere out of sight, where it can’t trouble the assumptions we were already acting on.

Feedback matters because it is one of the few ways we ever learn that we are wrong. Most of us can go on for years acting on assumptions that no longer fit the world. Especially when those assumptions make us feel competent, justified, or familiar with ourselves. Without something that pushes back, error doesn’t correct itself. It simply settles in and becomes the often invisible background of our decisions.

Knowing when we’re wrong

Some ideas are structured so that nothing can ever count against them. “I’m just bad at math”, “people are always out to get me.” Self-fulfilling prophecies that stop functioning as explanations and instead are just comforting stories we tell ourselves.

I’ve found that one way to guard against this is to be clear, before acting, about what I expect to happen if I’m right. Without clearly set in advance, it is too easy to reinterpret any outcome as a success after the fact.

When I design a course, for example, I expect students to struggle at certain points and also have an idea of when that should resolve for most students. I often introduce implementation ambiguity early on because I believe it serves a pedagogical purpose. If students express some discomfort in how they should solve a problem in the first week, that feedback doesn’t challenge my course design.

But that only works if there’s a point where continued struggle would force me to rethink the design. I have to be specific about what confusion I expect, and what outcomes should justify it by the end. Otherwise, I’m just building up an excuse for unclear instruction as “intentional ambiguity,” and the line between pedagogy and sloppiness disappears.

The same pattern shows up in how we talk about ourselves. “I’m just someone who speaks my mind, it’s not my fault if people can’t handle it” resembles a description, but it serves as a shield. The question worth asking isn’t whether it feels true, but whether there’s any feedback that would make us reconsider it.

Feedback isn’t a score

I’ve seen people fail to accept compliments as often as they fail to accept criticism. We assume people are “just being nice.” Sometimes that’s fine — if people tell you you’re beautiful all day it’s probably good not to let it go to your head. On the other hand, if your students tell you that you look like Minecraft Steve, well, welcome to my life.

But when people consistently praise our skills and we wave it off, we end up underestimating what we’re ready for. We don’t take on challenges we could handle because we discount positive signal as easily as negative. Feedback isn’t only useful for correction. It’s often the push we need to take on something bigger.

The problem is how we frame it. If feedback is primarily evaluation (good or bad, constructive or unhelpful) then our job is to judge whether it’s accurate. Judging is a short step from dismissing. Not “is it true?” or “is it fair?” but “what does it mean that someone walked away holding this belief?” Does that change anything?

When I was a director at Amazon, long, long ago, someone on my team once told me I was scary. After they got to know me, they realized I wasn’t as scary… but they were still a little scared.

My first reaction was that this seemed ridiculous. I’m not scary; I’m kind.

I asked what made them feel that way. They said in meetings, when people would say things, I would tear apart their arguments, ask how they knew something to be true. They worried that if they spoke, they wouldn’t be able to back up what they said. I did it in a “nice” way (calm, smiling), but that almost made it worse. Like I was an analytical machine ready to point out their every flaw.

This sounded like good leadership. I was an Amazonian; I was insisting on high standards, diving deep, teaching my team to be right, a lot. Those instincts got me to where I was. But by then I was a director with a large team, and the way you act carries more weight when you have power over people’s careers. I wasn’t encouraging rigor. I was shutting down conversation. At least when I was in the room.

Who is worth listening to?

When I give feedback to students or employees, they usually want more. More than I often feel I can give. They’re gracious and frequently grateful. They ask follow-up questions. The dynamic is easy. I have credibility; I’m expected to evaluate; and what I say might affect their grade or their career. Everything lines up. Most people can tell themselves they are open to feedback. Because in some situations, when delivered by some people, they are eager to listen.

Reverse the direction and see how quickly this falls apart.

Upward feedback, and I’m using that term broadly, is easy to dismiss. “Who are you to tell me how to do my job?” Subordinate to manager, patient to doctor, student to teacher, user to product manager. And, often, the skepticism is warranted; people without expertise tend to give bad advice.

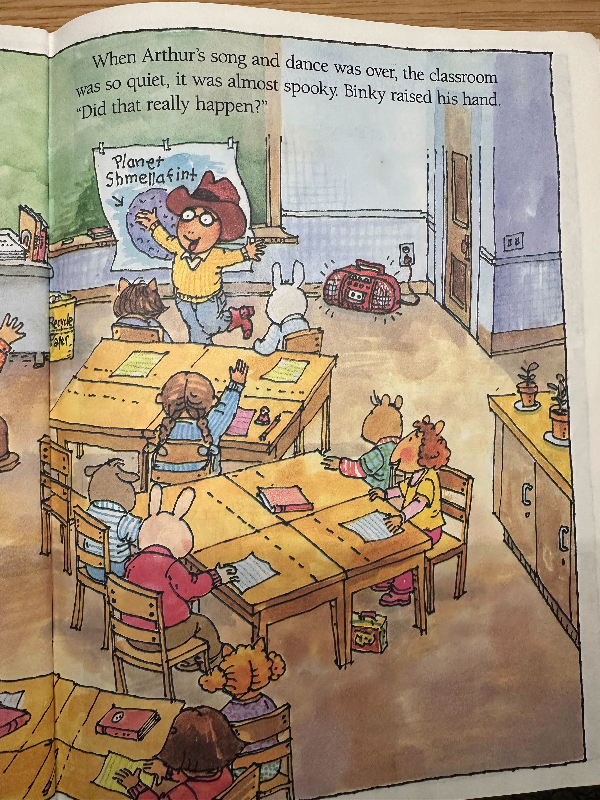

In “Arthur Writes a Story,” Arthur asks for feedback on a simple story about a boy finding his puppy. Each person suggests adding their favorite element from their own stories. They are not so much engaging with Arthur’s story as they are invested in their own. By the end, Arthur’s story has metamorphasized into a science fiction rock opera comedy about space-elephants. “Listen to feedback” cannot mean “do whatever people tell you.”

It’s a mistake to treat this insight as a license to dismiss categories of feedback entirely. The signal is rarely the literal suggestion. Arthur’s friends gave bad advice, but it doesn’t mean they couldn’t still provide useful feedback. The real skill is taking the time to understand why someone reacted the way they did, not just what they proposed as a solution. And then innovate based on what that reaction tells you.

When we reject feedback because it’s framed poorly or comes from someone without expertise, we lose the ability to understand how the people affected by our work are actually receiving it. A patient can’t tell a doctor how to practice medicine. But a patient knows when they feel unheard, confused, or scared. That’s a valuable perspective only they can give. Ignoring it doesn’t make you more expert. It just makes you blind to how it feels to be on the receiving end.

Genuine feedback is earned

People who don’t like us sometimes say things to hurt us. But, especially in professional contexts, they are often stating something true. The truth is often a better weapon than pure falsehood. I saw this pattern repeatedly as a manager and now as a teacher. Two people would not get along. They’d both point out the other person’s flaws. The criticism was often wrapped in assumed bad intentions, but underneath it calls out something observably true.

“Jack has no respect for other people. He is always late to meetings and when he does arrive derails the conversation to talk about things that don’t matter.” Is this feedback framed well? No. Does it give us some signal we can learn from, especially when combined with other details and perspectives? Absolutely.

For every blunt response like above, you’d get its more oblique cousin. “I love Jack, he is so helpful. It can be disruptive sometimes though how he arrives late to our morning meeting. I know he takes the bus here, and it isn’t really his fault, but maybe we can move the meeting?”

When you deliver the feedback, “it is important that you arrive on time for our morning meeting.” The response is too often either “I can’t help it” or, far worse, “who said that?”

The urge is understandable. Negative anonymous feedback makes me want to play detective about who said it. If I can discredit the source’s motives or expertise, I don’t have to engage with the substance. But that habit leads to a dark, unproductive relationship with feedback. It’s healthier to start by treating it in good faith unless you have evidence otherwise.

The dangerous part of this reaction is that even if you are right, you are signaling how you handle feedback. If you react with anger, or defensively, or sullenly, it causes those who value their relationship with you to hesitate next time. They learn to circle around. The unvarnished truth becomes something only your detractors will offer.

When you respond differently, with genuine curiosity and visible change, then giving you feedback becomes a relationship-strengthening act. People who care about you start to speak up.

Honest feedback from someone who cares about you is often not a gift; it is something you’ve earned through your reactions to feedback in the past.